The statistics from the Western Transportation Institute say that between 1 and 2 million large animals are killed by motorists every year.

Most of these animals are killed while trying to cross the road and migrate or find food in what was once their natural habitat.

Today there are 21 species that have been listed as endangered specifically because of highway deaths. These include the Key Deer in Florida, bighorn sheep in California and red-bellied turtles in Alabama.

Wild animals can’t migrate or search for food because of the highways. This in turn leads to inbreeding, weak offspring and potential extinction.

“Localized extinction happens when populations can’t find each other, and if they don’t have genetic variability, they will blink out—especially low-mobility species in old-growth forest,” Patty Garvey-Darda, a wildlife biologist with the U.S. Forest Service told National Geographic.

Animal road collisions hurt people too. On average, 200 humans are killed in such accidents. The costs are huge both in medical bills as in car repairs and roadside help.

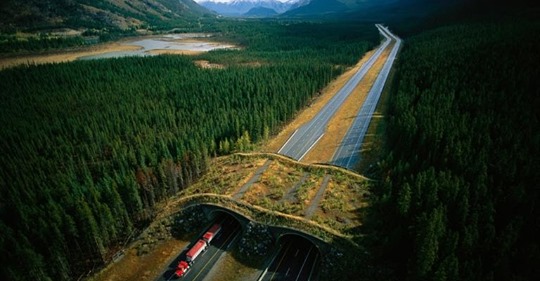

How wildlife bridges help

Over and under wildlife passes have been found to be extremely effective at preventing collisions and saving many animals.

Studies done on native species in Florida, bandicoots and wallabies in Australia, and Jaguars in Mexico have proven this.

“You can get reductions of 85 to 95 percent with crossings and fencing that guide animals under or over highways,” Rob Ament, road ecology program manager at the Western Transportation Institute told National Geographic.

These types of bridges and crossing have been popular in Europe since the 50’s and are now becoming popular everywhere.

Over-crossings look just like the regular highway crossing, except they are made to be like the natural habitat of the animals, enticing them to cross there.

Under-crossings are usually tunnels under highways that help small animals migrate.

Snoqualmie Pass in Washington state has a wildlife bridge being constructed right now, with native flora set to be planted in 2020, yet animals are already crossing it.

Over 20 over and under passes in the area will soon allow bears, mountain lions and even trout to move over what was before a deadly obstacle.

“Grizzly bears, elk, deer, and moose prefer big structures that are open,” says Tony Clevenger, a wildlife biologist at WTI , who monitors 6 overpasses and 38 underpasses at Banff National Park, where accidents have been reduced by 90 percent.

“Cougars and black bears prefer smaller, more constricted crossings, with less light and more cover.”